In which that eccentric detective novelist Mrs Oliver is called in to organise a Murder Hunt at a village fete but she suspects all is not as it should be and so asks Hercule Poirot to make sense of her suspicions. All seems well at first until an unexpected murder takes place in the boathouse! Even though the victim provides Poirot a huge clue at first hand before their death, Poirot can’t see the wood for trees until the final few chapters, when all is explained. As usual, if you haven’t read the book yet, don’t worry, I promise not to reveal whodunit!

In which that eccentric detective novelist Mrs Oliver is called in to organise a Murder Hunt at a village fete but she suspects all is not as it should be and so asks Hercule Poirot to make sense of her suspicions. All seems well at first until an unexpected murder takes place in the boathouse! Even though the victim provides Poirot a huge clue at first hand before their death, Poirot can’t see the wood for trees until the final few chapters, when all is explained. As usual, if you haven’t read the book yet, don’t worry, I promise not to reveal whodunit!

The book is dedicated “To Humphrey & Peggie Trevelyan”. Humphrey Trevelyan – also known as Baron Trevelyan, was a British diplomat and author, and, at the time of the publication of Dead Man’s Folly, was the British Ambassador to Egypt, which is doubtless how Agatha and Max Mallowan came to know him and his wife Peggie. Dead Man’s Folly was first published in the US in three abridged instalments in the Collier’s Weekly in July and August 1956, and in the UK in six abridged instalments in John Bull magazine in August and September 1956. The full book was first published the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in October 1956, and in the UK by Collins Crime Club on 5th November 1956.

The book is dedicated “To Humphrey & Peggie Trevelyan”. Humphrey Trevelyan – also known as Baron Trevelyan, was a British diplomat and author, and, at the time of the publication of Dead Man’s Folly, was the British Ambassador to Egypt, which is doubtless how Agatha and Max Mallowan came to know him and his wife Peggie. Dead Man’s Folly was first published in the US in three abridged instalments in the Collier’s Weekly in July and August 1956, and in the UK in six abridged instalments in John Bull magazine in August and September 1956. The full book was first published the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in October 1956, and in the UK by Collins Crime Club on 5th November 1956.

Dead Man’s Folly is a curious book in a number of ways. At first, it strongly reminded me of The Hollow, with Lady Stubbs taking on the latter-day role of Lady Angkatell. But then the story goes in a different direction, and for many pages in the centre sections of the book, it appears to lose its way, as we wait for something specific to happen. The thing we’re waiting for never actually materialises either, which also feels a bit of a disappointment. Poirot, unforgivably, ignores a vital clue which the reader picks up on immediately; it’s not often that we outsmart Poirot, and it simply doesn’t sit well. When we finally understand the truth of the case, the plot feels overwhelmingly complex and intricate. Many of the characters, too, are just lightly sketched in, and even the return of Mrs Oliver doesn’t portray her as exciting and vivid as we remember her from before. Even the title isn’t particularly suitable; yes, there is the double meaning of the word folly but I’m blowed if I can work out who the Dead Man might be.

Dead Man’s Folly is a curious book in a number of ways. At first, it strongly reminded me of The Hollow, with Lady Stubbs taking on the latter-day role of Lady Angkatell. But then the story goes in a different direction, and for many pages in the centre sections of the book, it appears to lose its way, as we wait for something specific to happen. The thing we’re waiting for never actually materialises either, which also feels a bit of a disappointment. Poirot, unforgivably, ignores a vital clue which the reader picks up on immediately; it’s not often that we outsmart Poirot, and it simply doesn’t sit well. When we finally understand the truth of the case, the plot feels overwhelmingly complex and intricate. Many of the characters, too, are just lightly sketched in, and even the return of Mrs Oliver doesn’t portray her as exciting and vivid as we remember her from before. Even the title isn’t particularly suitable; yes, there is the double meaning of the word folly but I’m blowed if I can work out who the Dead Man might be.

Nevertheless, there are some very enjoyable sequences, and, if not well-written characters, then well-written conversations. There’s a light comic touch, for example, to Poirot’s lengthy interrogation of Miss Brewis, punctuated by him slowly looking for the breakfast toast and jam. As I said just now, the return of Mrs Oliver is enjoyable, but not outstanding; but a few further insights are made into Hercule Poirot’s character which redress the balance somewhat on the otherwise sketchy characterisations. In fact, we probably learn more about him in this book than in any other, save, perhaps for the first couple of books where the character was first introduced. We’ve seen before his disapproval of how some young women don’t make the best of their appearance. It’s elaborated on more in this book. When he meets a couple of girls from the local youth hostel, “he was reflecting, not for the first time, that seen from the back, shorts were becoming to very few of the female sex. He shut his eyes in pain. Why, oh why, must young women array themselves thus? Those scarlet thighs were singularly unattractive!” Before you call him a sexist pig, remember he is from a different era. But sexist pig does somewhat come to mind.

Nevertheless, there are some very enjoyable sequences, and, if not well-written characters, then well-written conversations. There’s a light comic touch, for example, to Poirot’s lengthy interrogation of Miss Brewis, punctuated by him slowly looking for the breakfast toast and jam. As I said just now, the return of Mrs Oliver is enjoyable, but not outstanding; but a few further insights are made into Hercule Poirot’s character which redress the balance somewhat on the otherwise sketchy characterisations. In fact, we probably learn more about him in this book than in any other, save, perhaps for the first couple of books where the character was first introduced. We’ve seen before his disapproval of how some young women don’t make the best of their appearance. It’s elaborated on more in this book. When he meets a couple of girls from the local youth hostel, “he was reflecting, not for the first time, that seen from the back, shorts were becoming to very few of the female sex. He shut his eyes in pain. Why, oh why, must young women array themselves thus? Those scarlet thighs were singularly unattractive!” Before you call him a sexist pig, remember he is from a different era. But sexist pig does somewhat come to mind.

Possibly Poirot’s problem is that he is an old romantic. We already know of his passion for the Countess Vera from previous books. In Dead Man’s Folly, Poirot tells Sally Legge where English husbands get it wrong, and “foreigners are more gallant”. ““We know,” said Poirot, “that it is necessary to tell a woman at least once a week, and preferably three or four times, that we love her; and that it also wise to bring her a few flowers, to pay her a few compliments, to tell her that she looks well in her new dress or her new hat.”” When Sally asks him if he practices what he preaches, he replies, “I, Madame, am not a husband […] alas! […] it is terrible all that I have missed in life.”

Possibly Poirot’s problem is that he is an old romantic. We already know of his passion for the Countess Vera from previous books. In Dead Man’s Folly, Poirot tells Sally Legge where English husbands get it wrong, and “foreigners are more gallant”. ““We know,” said Poirot, “that it is necessary to tell a woman at least once a week, and preferably three or four times, that we love her; and that it also wise to bring her a few flowers, to pay her a few compliments, to tell her that she looks well in her new dress or her new hat.”” When Sally asks him if he practices what he preaches, he replies, “I, Madame, am not a husband […] alas! […] it is terrible all that I have missed in life.”

Some more of Poirot’s homespun philosophy: in conversation with Alec Legge, who believes that “in times of stress, when it’s a matter of life or death, one can’t think of one’s own insignificant ills or preoccupations”, Poirot takes the opposite view. “I assure you, you are quite wrong. In the late war, during a severe air-raid, I was much less preoccupied by the thought of death than of the pain from a corn on my little toe. It surprised me at the time that it should be so. “Think”, I said to myself, “at any moment now, death may come,” But I was still conscious of my corn – indeed I felt injured that I should have that to suffer as well as the fear of death. It was because I might die that every small personal matter in my life acquired increased importance. I have seen a woman knocked down in a street accident, with a broken leg, and she has burst out crying because she sees that there is a ladder in her stocking.” I guess this very much sums up Poirot’s belief that people always behave like people – and that’s how they give themselves away when it comes to matters of crime. It also surprises one that Poirot should have been actively at war during the First World War – The Mysterious Affair at Styles confirms that Poirot arrived as a refugee in England after the war and had been an active member of the Belgian Police Force – but we know of no military involvement. Maybe he was unlucky in a street somewhere.

Some more of Poirot’s homespun philosophy: in conversation with Alec Legge, who believes that “in times of stress, when it’s a matter of life or death, one can’t think of one’s own insignificant ills or preoccupations”, Poirot takes the opposite view. “I assure you, you are quite wrong. In the late war, during a severe air-raid, I was much less preoccupied by the thought of death than of the pain from a corn on my little toe. It surprised me at the time that it should be so. “Think”, I said to myself, “at any moment now, death may come,” But I was still conscious of my corn – indeed I felt injured that I should have that to suffer as well as the fear of death. It was because I might die that every small personal matter in my life acquired increased importance. I have seen a woman knocked down in a street accident, with a broken leg, and she has burst out crying because she sees that there is a ladder in her stocking.” I guess this very much sums up Poirot’s belief that people always behave like people – and that’s how they give themselves away when it comes to matters of crime. It also surprises one that Poirot should have been actively at war during the First World War – The Mysterious Affair at Styles confirms that Poirot arrived as a refugee in England after the war and had been an active member of the Belgian Police Force – but we know of no military involvement. Maybe he was unlucky in a street somewhere.

Christie brings our attention back to Poirot’s need and desire for symmetrically ordered design. “Hercule Poirot sat in a square chair in front of the square fireplace in the square room of his London flat. In front of him were various objects that were not square: that were instead violently and almost impossibly curved. Each of them, studied separately, looked as if they could not have any conceivable function in a sane world. They appeared improbable, irresponsible, and wholly fortuitous […] Assembled in their proper place in their particular universe, they not only made sense, they made a picture. In other words, Hercule Poirot was doing a jigsaw puzzle.” Thus Christie emphasises Poirot’s obsession with neatness and regularity, and also shows that a jigsaw is the perfect metaphor for how he pieces together the individual facts of a case in order to create the whole picture.

Christie brings our attention back to Poirot’s need and desire for symmetrically ordered design. “Hercule Poirot sat in a square chair in front of the square fireplace in the square room of his London flat. In front of him were various objects that were not square: that were instead violently and almost impossibly curved. Each of them, studied separately, looked as if they could not have any conceivable function in a sane world. They appeared improbable, irresponsible, and wholly fortuitous […] Assembled in their proper place in their particular universe, they not only made sense, they made a picture. In other words, Hercule Poirot was doing a jigsaw puzzle.” Thus Christie emphasises Poirot’s obsession with neatness and regularity, and also shows that a jigsaw is the perfect metaphor for how he pieces together the individual facts of a case in order to create the whole picture.

Inspector Bland, one of a team of policemen that we meet in this book for the one and only time, is perhaps less insightful regarding his opinion of Poirot – initially, at least. PC Hoskins asks him who Poirot is; his response: “you’d describe him probably as a scream […] Kind of music hall parody of a Frenchman, but actually he’s a Belgian. But in spite of his absurdities, he’s got brains.” High praise indeed! For me, the most interesting insight into Poirot’s mentality is his disappointment not to have solved the case earlier. “He went slowly out of the boathouse, unhappy and displeased with himself. He, Hercule Poirot, had been summoned to prevent a murder – and he had not prevented it. It had happened. What was even more humiliating was that he had no real ideas even now, as to what had actually happened. It was ignominious. And tomorrow he must return to London defeated. His ego was seriously deflated – even his moustaches drooped.”

Inspector Bland, one of a team of policemen that we meet in this book for the one and only time, is perhaps less insightful regarding his opinion of Poirot – initially, at least. PC Hoskins asks him who Poirot is; his response: “you’d describe him probably as a scream […] Kind of music hall parody of a Frenchman, but actually he’s a Belgian. But in spite of his absurdities, he’s got brains.” High praise indeed! For me, the most interesting insight into Poirot’s mentality is his disappointment not to have solved the case earlier. “He went slowly out of the boathouse, unhappy and displeased with himself. He, Hercule Poirot, had been summoned to prevent a murder – and he had not prevented it. It had happened. What was even more humiliating was that he had no real ideas even now, as to what had actually happened. It was ignominious. And tomorrow he must return to London defeated. His ego was seriously deflated – even his moustaches drooped.”

One final thing on Poirot – we get to find out his phone number! It’s Trafalgar 8137. When those London area names became numbers, that would have changed to 872-8137; then in 1968 the codes changed and Poirot’s number would have become 01 839 8137 – and now, 0207 839 8137. Hugely disappointing to discover that the number appears to be currently unused.

One final thing on Poirot – we get to find out his phone number! It’s Trafalgar 8137. When those London area names became numbers, that would have changed to 872-8137; then in 1968 the codes changed and Poirot’s number would have become 01 839 8137 – and now, 0207 839 8137. Hugely disappointing to discover that the number appears to be currently unused.

Enough of Poirot! Let’s move on to Mrs Oliver, if I can put it like that. You’ll remember from her previous appearances that her trademark symbol is the apple, and once again, when we meet Mrs O for the first time in this book, “several apples fell from her lap and rolled in all directions”. She’s obsessed with the things. I can’t wait to re-read Hallowe’en Party, where Mrs Oliver discovers that apples can have a more sinister side. Poirot values Mrs Oliver’s company and instinct – it’s on her say-so that he ups and leaves the comfort of his London flat for Devon. Whilst we may feel she represents Christie herself, with her insights into writing detective novels, Poirot sees her as a replacement Hastings. Towards the end of the book she makes an innocent comment about hats being a symbol, and Poirot sees the light on one aspect of the crime that’s been bothering him. Mrs Oliver hasn’t a clue that she’s helped. “It is extraordinary,” said Poirot, and his voice was awed. “Always you give me ideas. So also did my friend Hastings whom I have not seen for many, many years. You have given me now the clue to yet another piece of my problem.” Unfortunately she fades out of the book for a long spell in the middle and only reappears right at the end, which I feel is rather unbalanced.

Enough of Poirot! Let’s move on to Mrs Oliver, if I can put it like that. You’ll remember from her previous appearances that her trademark symbol is the apple, and once again, when we meet Mrs O for the first time in this book, “several apples fell from her lap and rolled in all directions”. She’s obsessed with the things. I can’t wait to re-read Hallowe’en Party, where Mrs Oliver discovers that apples can have a more sinister side. Poirot values Mrs Oliver’s company and instinct – it’s on her say-so that he ups and leaves the comfort of his London flat for Devon. Whilst we may feel she represents Christie herself, with her insights into writing detective novels, Poirot sees her as a replacement Hastings. Towards the end of the book she makes an innocent comment about hats being a symbol, and Poirot sees the light on one aspect of the crime that’s been bothering him. Mrs Oliver hasn’t a clue that she’s helped. “It is extraordinary,” said Poirot, and his voice was awed. “Always you give me ideas. So also did my friend Hastings whom I have not seen for many, many years. You have given me now the clue to yet another piece of my problem.” Unfortunately she fades out of the book for a long spell in the middle and only reappears right at the end, which I feel is rather unbalanced.

Let’s look at some of Mrs Oliver’s insights into the writing process. When Poirot is impressed at her ingenuity in planning a torturously complicated story for the Murder Hunt, she replies, “it’s never difficult to think of things […] the trouble is that you think of too many, and then it all becomes too complicated, so you have to relinquish some of them and that is rather agony.” Later she admits that it’s possible to make a mistake. “”Don’t bother about me,” she said to Poirot. “I’m just remembering if there’s anything I’ve forgotten.” Sir George laughed heartily. “The fatal flaw, eh?” he remarked. “That’s just it,” said Mrs Oliver. “There always is one. Sometimes one doesn’t realise it until a book’s actually in print. And then it’s agony!” Her face reflected this emotion. She sighed. “The curious thing is that most people never notice it. I say to myself, “but of course the cook would have been bound to notice that two cutlets hadn’t been eaten,” but nobody else thinks of it at all.”” I believe Christie herself admitted that there are a few errors in her books; there are chronology discrepancies in Crooked House and Murder in Mesopotamia, I think; and the murder weapon in Death in the Clouds was the wrong size for an aeroplane!

Let’s look at some of Mrs Oliver’s insights into the writing process. When Poirot is impressed at her ingenuity in planning a torturously complicated story for the Murder Hunt, she replies, “it’s never difficult to think of things […] the trouble is that you think of too many, and then it all becomes too complicated, so you have to relinquish some of them and that is rather agony.” Later she admits that it’s possible to make a mistake. “”Don’t bother about me,” she said to Poirot. “I’m just remembering if there’s anything I’ve forgotten.” Sir George laughed heartily. “The fatal flaw, eh?” he remarked. “That’s just it,” said Mrs Oliver. “There always is one. Sometimes one doesn’t realise it until a book’s actually in print. And then it’s agony!” Her face reflected this emotion. She sighed. “The curious thing is that most people never notice it. I say to myself, “but of course the cook would have been bound to notice that two cutlets hadn’t been eaten,” but nobody else thinks of it at all.”” I believe Christie herself admitted that there are a few errors in her books; there are chronology discrepancies in Crooked House and Murder in Mesopotamia, I think; and the murder weapon in Death in the Clouds was the wrong size for an aeroplane!

When Mrs Oliver returns to the story towards the end of the book, she has been preparing for – or rather not preparing for – a talk she had been asked to give entitled “ How I Write My Books”. But it’s a question she can’t answer. “I mean, what can you say about how you write books? What I mean is, first you’ve got to think of something, and when you’ve thought of it you’ve got to force yourself to sit down and write it. That’s all. It would have taken me just three minutes to explain that, and then the Talk would have been ended and everyone would have been very fed up. I can’t imagine why everybody is always so keen for authors to talk about writing. I should have thought it was an author’s business to write, not talk.” I’m guessing Mrs Christie didn’t much like giving talks.

When Mrs Oliver returns to the story towards the end of the book, she has been preparing for – or rather not preparing for – a talk she had been asked to give entitled “ How I Write My Books”. But it’s a question she can’t answer. “I mean, what can you say about how you write books? What I mean is, first you’ve got to think of something, and when you’ve thought of it you’ve got to force yourself to sit down and write it. That’s all. It would have taken me just three minutes to explain that, and then the Talk would have been ended and everyone would have been very fed up. I can’t imagine why everybody is always so keen for authors to talk about writing. I should have thought it was an author’s business to write, not talk.” I’m guessing Mrs Christie didn’t much like giving talks.

One last observation about Mrs Oliver – Christie wryly mentions that three years after the case “Hercule Poirot read The Woman in the Wood by Ariadne Oliver, and wondered whilst he read it why some of the persons and incidents seemed to him vaguely familiar.” As Pablo Picasso once said, “good artists copy, great artists steal.”

One last observation about Mrs Oliver – Christie wryly mentions that three years after the case “Hercule Poirot read The Woman in the Wood by Ariadne Oliver, and wondered whilst he read it why some of the persons and incidents seemed to him vaguely familiar.” As Pablo Picasso once said, “good artists copy, great artists steal.”

This book is surprisingly full of other police types. Normally Poirot solves a case either on his own or in company with the local police inspector or someone from Scotland Yard. Occasionally they also involve the Chief Constable. Dead Man’s Folly, however, features at least five other police officers. It’s almost as though Christie was trying them out for size to see if they were worth resurrecting in future books. I’ve already referred to Inspector Bland; bland by name, bland by nature. Christie primarily uses him as an all-purpose cop, programmed to ask questions of suspects, rather than an individual with his own personality. “You’re so damned respectable, Bland”, says Major Merrell, his Chief Constable. All we know of Merrell is that Christie tells us he “had irritable tufted eyebrows and looked rather like an angry terrier. But his men all liked him and respected his judgment.” There’s also Superintendent Baldwin, Bland’s immediate superior (we presume), of which we know that he is “a large comfortable-looking man”, whatever that means. We briefly meet Sergeant Cottrell, “a brisk young man with a good opinion of himself, who always managed to annoy his superior officer.” And there’s PC Hoskins, who’s not that PC after all. Hoskins is one of those lesser police officers who listen to the local gossip, and mistrust anyone who wasn’t born in the same village that he was. But we do understand that he is “a man of inquisitive mind with a great interest in everybody and everything”. If there’s a suspect, he’s bound to be a “”foreigner of some sort”, “one of those that stop up to the Hostel at Hoodown, likely as not, There’s some queer ones among them – and a lot of goings-on […] you never know with foreigners. Turn nasty, they can, all in a moment […]” Bland reflected that the local verdict seemed to be the comfortable and probably age-long one of attributing every tragic occurrence to unspecified foreigners.”

This book is surprisingly full of other police types. Normally Poirot solves a case either on his own or in company with the local police inspector or someone from Scotland Yard. Occasionally they also involve the Chief Constable. Dead Man’s Folly, however, features at least five other police officers. It’s almost as though Christie was trying them out for size to see if they were worth resurrecting in future books. I’ve already referred to Inspector Bland; bland by name, bland by nature. Christie primarily uses him as an all-purpose cop, programmed to ask questions of suspects, rather than an individual with his own personality. “You’re so damned respectable, Bland”, says Major Merrell, his Chief Constable. All we know of Merrell is that Christie tells us he “had irritable tufted eyebrows and looked rather like an angry terrier. But his men all liked him and respected his judgment.” There’s also Superintendent Baldwin, Bland’s immediate superior (we presume), of which we know that he is “a large comfortable-looking man”, whatever that means. We briefly meet Sergeant Cottrell, “a brisk young man with a good opinion of himself, who always managed to annoy his superior officer.” And there’s PC Hoskins, who’s not that PC after all. Hoskins is one of those lesser police officers who listen to the local gossip, and mistrust anyone who wasn’t born in the same village that he was. But we do understand that he is “a man of inquisitive mind with a great interest in everybody and everything”. If there’s a suspect, he’s bound to be a “”foreigner of some sort”, “one of those that stop up to the Hostel at Hoodown, likely as not, There’s some queer ones among them – and a lot of goings-on […] you never know with foreigners. Turn nasty, they can, all in a moment […]” Bland reflected that the local verdict seemed to be the comfortable and probably age-long one of attributing every tragic occurrence to unspecified foreigners.”

Now we’ll look at some of the references in this book. Starting with the locations, this book is set primarily in Devon, but bookended with Poirot’s flat in London. Nasse House, the prime location for the story, is in the appropriately named Nassecombe, other local towns and villages to appear are Helm, Helmmouth, Brixwell and Gitcham. All of these place names are fictitious; however, I think it’s likely that the setting is very much inspired by Christie’s own home Greenaway near Dartmouth, and that Helmmouth is Dartmouth, Brixwell is Brixham, Gitcham is Dittisham, and Nasse House and Nassecombe are equated with Noss near Dartmouth.

Now we’ll look at some of the references in this book. Starting with the locations, this book is set primarily in Devon, but bookended with Poirot’s flat in London. Nasse House, the prime location for the story, is in the appropriately named Nassecombe, other local towns and villages to appear are Helm, Helmmouth, Brixwell and Gitcham. All of these place names are fictitious; however, I think it’s likely that the setting is very much inspired by Christie’s own home Greenaway near Dartmouth, and that Helmmouth is Dartmouth, Brixwell is Brixham, Gitcham is Dittisham, and Nasse House and Nassecombe are equated with Noss near Dartmouth.

There are a few other references, mostly pretty well known or guessable, with just a couple that foxed me. When Poirot observes Lady Stubbs’ immaculate fingernails, he thinks “they toil not, neither do they spin…” which is taken from the Bible, the gospel of Matthew, Chapter 6, verses 28-29: “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: and yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.” I remember having to read that at a school assembly once. When Sally tells Sir George that he reminded her of Betsy Trotwood shouting at donkeys, he doesn’t get the reference, but you and I both know that’s David Copperfield’s aunt.

There are a few other references, mostly pretty well known or guessable, with just a couple that foxed me. When Poirot observes Lady Stubbs’ immaculate fingernails, he thinks “they toil not, neither do they spin…” which is taken from the Bible, the gospel of Matthew, Chapter 6, verses 28-29: “Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: and yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these.” I remember having to read that at a school assembly once. When Sally tells Sir George that he reminded her of Betsy Trotwood shouting at donkeys, he doesn’t get the reference, but you and I both know that’s David Copperfield’s aunt.

Mrs Folliat quotes some lines of Spenser to Poirot: “Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas, ease after war, death after life, doth greatly please…” which are the last two lines of his poem Sleep After Toyle, from his collection of short poems entitled Complaints, published in 1591, which I confess I had never come across. Mrs Masterton tells Poirot that Sir George’s name was possibly taken from Lord George Sanger’s Circus. George Sanger was a travelling showman and circus proprietor active in the 19th century, who established his circus at an amphitheatre on Westminster Bridge Road in London.

Mrs Folliat quotes some lines of Spenser to Poirot: “Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas, ease after war, death after life, doth greatly please…” which are the last two lines of his poem Sleep After Toyle, from his collection of short poems entitled Complaints, published in 1591, which I confess I had never come across. Mrs Masterton tells Poirot that Sir George’s name was possibly taken from Lord George Sanger’s Circus. George Sanger was a travelling showman and circus proprietor active in the 19th century, who established his circus at an amphitheatre on Westminster Bridge Road in London.

“When lovely woman stoops to folly” quotes Mrs Oliver, without knowing where she’s heard it before. It’s the title and first line of a short poem by Oliver Goldsmith – I wonder if Christie was punning on the name Oliver as a private joke? When Weyman is asked if he had seen Lady Stubbs on the afternoon of the fete, he replies “Of course I saw her, Who could miss her? Dressed up like a mannequin of Jacques Fath or Christian Dior?” Dior, of course, is very familiar. But Fath? He was a French fashion designer, whose clients included Ava Gardner, Greta Garbo and Rita Heyworth, and he even dressed Eva Peron. He died of leukaemia at the age of 42, two years before Dead Man’s Folly was published. Finally, Major Merrall concludes that Lady Stubbs was not a wealthy woman, in fact “she’s not got a stiver of her own”. I’d never come across the word stiver before. It derives from the Dutch, stuiver, which was an old coin, the equivalent of five Dutch cents, a 20th of a guilder. My OED tells me it came into use in English in the early 17th century. Who knew?

“When lovely woman stoops to folly” quotes Mrs Oliver, without knowing where she’s heard it before. It’s the title and first line of a short poem by Oliver Goldsmith – I wonder if Christie was punning on the name Oliver as a private joke? When Weyman is asked if he had seen Lady Stubbs on the afternoon of the fete, he replies “Of course I saw her, Who could miss her? Dressed up like a mannequin of Jacques Fath or Christian Dior?” Dior, of course, is very familiar. But Fath? He was a French fashion designer, whose clients included Ava Gardner, Greta Garbo and Rita Heyworth, and he even dressed Eva Peron. He died of leukaemia at the age of 42, two years before Dead Man’s Folly was published. Finally, Major Merrall concludes that Lady Stubbs was not a wealthy woman, in fact “she’s not got a stiver of her own”. I’d never come across the word stiver before. It derives from the Dutch, stuiver, which was an old coin, the equivalent of five Dutch cents, a 20th of a guilder. My OED tells me it came into use in English in the early 17th century. Who knew?

Which brings me nicely to the question of money, and regular readers will know that I like to consider any significant sums of money in Christie’s books and work out what their value would be today, just to get a feel of the range of sums that we’re looking at. There are no grand values bandied about in this book, rather the opposite in fact. Admission to the fete cost half-a-crown (that’s 12.5p to you youngsters) – at today’s rate that would be just over £2. Bargain, I’d say. And Lady Stubbs tells Poirot that she once won sixty thousand francs at Monte Carlo on the roulette wheel. Unfortunately, she doesn’t tell us exactly when, but even in 1956 that would have been the equivalent of over £8000 today – so not a bad win at all.

Which brings me nicely to the question of money, and regular readers will know that I like to consider any significant sums of money in Christie’s books and work out what their value would be today, just to get a feel of the range of sums that we’re looking at. There are no grand values bandied about in this book, rather the opposite in fact. Admission to the fete cost half-a-crown (that’s 12.5p to you youngsters) – at today’s rate that would be just over £2. Bargain, I’d say. And Lady Stubbs tells Poirot that she once won sixty thousand francs at Monte Carlo on the roulette wheel. Unfortunately, she doesn’t tell us exactly when, but even in 1956 that would have been the equivalent of over £8000 today – so not a bad win at all.

Now it’s time for my usual at-a-glance summary, for Dead Man’s Folly:

Publication Details: 1956. My copy is a Fontana paperback, fourth impression, dated September 1974, with a price of 35p on the back cover. The cover illustration by Tom Adams shows a dead girl clutching a scarf, lying on a bed of daisies under a folly and with a yacht in the distance. That basically brings together many elements of the book although it takes liberties with what actually happened!

How many pages until the first death: 64. It feels like quite a long wait, but you do get a sense of pre-murder suspense; you know something evil is going to happen to someone but you don’t know what and you don’t know to whom.

Funny lines out of context: A classic use of the E word, in a conversation between Mrs Oliver and Hercule Poirot.

“I beg your pardon, M. Poirot, did you say something?” “It was an ejaculation only.”

Memorable characters:

Unfortunately, this is one aspect in which this book falls down badly, and is one reason why it becomes a curious re-read, in that it’s so unmemorable, it’s like you’re reading it for the first time!

Christie the Poison expert:

Again, nothing to see here. Christie’s chosen methods of murder in this book are garrotting and drowning.

Class/social issues of the time:

This book isn’t as rooted in social issues as much as many of Christie’s other works, but there are a few interesting points of note. The growth of Communism continues to vex Christie, a theme she introduced in Destination Unknown and which continued in Hickory Dickory Dock. Here it’s not so strongly alluded to, and is also conflated with Christie’s regular observations about “foreigners”. The siting of the Youth Hostel at Hoodown upsets many of the villagers with its inevitable influx of young people from abroad. Sir George is not happy at this arrangement, especially as many of the young people try to use his land as a short cut. ““Trespassers are a menace since they’ve started this Youth Hostel tomfoolery. They come out at you from everywhere wearing the most incredible shirts – boy this morning had one all covered with crawling turtles and things – made me think I’d been hitting the bottle or something. Half of them can’t speak English – just gibber at you…” He mimicked: “ ‘Oh, plees – yes, haf you – tell me – iss way to ferry?” I say no, it isn’t, roar at them, and send them back where they’ve come from, but half the time they just blink and stare and don’t understand. And the girls giggle. All kinds of nationalities, Italian, Yugoslavian, Dutch, Finnish – Eskimos I shouldn’t be surprised! Half of them Communists, I shouldn’t wonder”, he ended darkly. “Come now, George, don’t get started on communists,” said Mrs Legge.”

But there’s also the curious incident of Alec Legge and the young man in the turtle shirt. The true significance of this is never made absolutely plain, but Poirot confronts the scientist over his deduction that “some years ago you had an interest and sympathy for a certain political party. Like many other young men of a scientific bent” – which takes us straight back to the Communist “paradise” in Destination Unknown. Poirot realises that there was an assignation between Legge and this young man in the boathouse. There is some suggestion, maybe, of espionage, or blackmail; we just don’t know. But whatever the reality, it’s clear that this is another reference to what was perceived to be the growing threat from the east.

There’s also a reiteration of an idea that I’ve seen in other Christie novels, and one which Poirot often employs to his own benefit. Miss Brewis doesn’t hold back from telling Poirot what she thinks about Lady Stubbs. ““Lady Stubbs knows perfectly well exactly what she is doing. Besides being, as you said, a very decorative young woman, she is also a very shrewd one.” She had turned away and left the room before Poirot’s eyebrows had fully risen in surprise. So that was what the efficient Miss Brewis thought, was it? Or had she merely said so for some reason of her own? And why had she made such a statement to him – to a newcomer? Because he was a newcomer, perhaps? And also because he was a foreigner. As Hercule Poirot had discovered by experience, there were many English people who considered that what one said to foreigners didn’t count!” For this to be true, it implies that the English consider foreigners to be less important, or intelligent, or relevant. Whatever, it’s a sign of international disrespect. Poirot recognises latent xenophobia in conversation with Mrs Masterton too. “”By the way, you’re a friend of the Eliots, I believe?” Poirot, after his long sojourn in England, comprehended that this was an indication of social recognition. Mrs Masterton was in fact saying: “Although a foreigner, I understand you are One of Us.” She continued to chat in an intimate manner.” Apart from that, there’s the usual, minor xenophobic banter you find in a typical Christie, including Sir George referring to De Sousa as a “dago”, as well as PC Hoskins’ non-PC comments I mentioned earlier.

Even though the book was published more than ten years after the end of the war, there are still traces of its after-effects. Mrs Masterton doesn’t trust Warburton; “silly the way he sticks to calling himself “Captain”. Not a regular soldier, and never within miles of a German.” Like Christopher Wren in Three Blind Mice (and by association, The Mousetrap) and Laurence Brown in Crooked House, people are still suspicious of any man without an immaculate war record.

But time marches on, and the 1950s bring with them the first signs of creature comforts that we have come to love and appreciate over the past seventy years. Mrs Folliat reflects on how the top cottage at Nasse House has been “enlarged and modernised […] it had to be; we’ve got quite a young man now as head gardener, with a young wife – and these young women must have electric irons and modern cookers and television, and all that. One must go with the times.” I think that’s the first time that Christie has mentioned such modern inventions – although I think we may have seen Poirot blissfully warmed by central heating in an earlier book. By 1956 I would have thought it would have been commonplace to have at least one of these modern items in your household. But then again, Mrs Folliat does rather live in the past.

Trust PC Hoskins to bring up the subject of Lady Stubbs’ IQ, suggesting it might be on the low side. “The inspector looked at him with annoyance. “Don’t bring out these new-fangled terms like a parrot. I don’t care if she’s got a high IQ or a low IQ.” Bland might consider IQ to be a new-fangled idea but in fact the concept of IQ had been around for decades. Maybe at this time it was just starting to gain popular traction.

Classic denouement: No. As in Hickory Dickory Dock before it, the identity of the murderer is revealed in a quiet private discussion purely between Poirot, Bland and Merrell; but then Christie cuts away from the scene before Poirot can explain to his colleagues How They Did It. Poirot then moves on to a discussion with a third party to seek clarification on certain points of his theories. Apart from that, we never see the culprit confronted with their crime, or see other witnesses find out what actually happened, or their reaction to the truth. Not at all satisfactory, I fear.

Happy ending? Unusually, there’s no reason to expect any happy ending here. No last-minute engagements, no rightful inheritances; in fact, there is a suspicion that one of the characters might end their own life after the end of the book. Very downbeat.

Did the story ring true? Whilst it’s not an impossible solution to the crime it’s a highly implausible one. Very complicated, very elaborate (and totally unguessable!) So, no, it doesn’t ring that true.

Overall satisfaction rating: It’s a complex plot, full of smoke and mirrors, and impossible to guess; it has a dull middle part where nothing much happens, and the characters and story aren’t particularly memorable. To its credit, it fleshes out Poirot a lot more, and there are some entertaining passages. But, overall, a slightly disappointing 7/10.

Thanks for reading my blog of Dead Man’s Folly and if you’ve read it too, I’d love to know what you think. Please just add a comment in the space below. Next up in the Agatha Christie Challenge is 4.50 from Paddington, and the return of Miss Marple. The Margaret Rutherford Marple film Murder She Said is based on this book, and I’ve recently seen the film again so I can clearly remember whodunit. We’ll see if that spoils the book at all. As usual, I’ll blog my thoughts about it as soon as I can. In the meantime, please read it too then we can compare notes! Happy sleuthing!

Thanks for reading my blog of Dead Man’s Folly and if you’ve read it too, I’d love to know what you think. Please just add a comment in the space below. Next up in the Agatha Christie Challenge is 4.50 from Paddington, and the return of Miss Marple. The Margaret Rutherford Marple film Murder She Said is based on this book, and I’ve recently seen the film again so I can clearly remember whodunit. We’ll see if that spoils the book at all. As usual, I’ll blog my thoughts about it as soon as I can. In the meantime, please read it too then we can compare notes! Happy sleuthing!

I’ve never liked Gilbert and Sullivan; go on, shoot me. I probably booked this in an attempt to see what I was missing, because I knew (and still do) so many people who think that G & S are a class act, and they can’t all be wrong. I have absolutely no memory of this show, so perhaps they are all wrong.

I’ve never liked Gilbert and Sullivan; go on, shoot me. I probably booked this in an attempt to see what I was missing, because I knew (and still do) so many people who think that G & S are a class act, and they can’t all be wrong. I have absolutely no memory of this show, so perhaps they are all wrong.

A jolly comedy, produced by the (at the time) ubiquitous Theatre of Comedy Company, written by Arne Sultan and Earl Barret (who? Mr Barret was a TV writer of shows such as Bewitched and My Three Sons, and Mr Sultan was his TV producer) directed by Ray Cooney, so you know precisely the kind of thing to expect, and starring Dinsdale Landen and Liza Goddard. It was very enjoyable and memorable for one main reason; it was the first time that I took a young Australian lady, Miss Duncansby, to the theatre, whilst she was on holiday in the UK. Little did I know that 28 months later she would become Mrs Chrisparkle.

A jolly comedy, produced by the (at the time) ubiquitous Theatre of Comedy Company, written by Arne Sultan and Earl Barret (who? Mr Barret was a TV writer of shows such as Bewitched and My Three Sons, and Mr Sultan was his TV producer) directed by Ray Cooney, so you know precisely the kind of thing to expect, and starring Dinsdale Landen and Liza Goddard. It was very enjoyable and memorable for one main reason; it was the first time that I took a young Australian lady, Miss Duncansby, to the theatre, whilst she was on holiday in the UK. Little did I know that 28 months later she would become Mrs Chrisparkle.

Well this show had a fairly mighty pedigree, so long as you like David Essex – he wrote the music and starred as Fletcher Christian. I do like David Essex – on records – but not on stage, where I feel he is wooden and expressionless, sadly. But there was more to this show than Mr Essex. Frank Finlay was Captain Bligh, whilst Sinitta Renet (yes, the Sinitta of So Macho fame, who had been going out with Simon Cowell, had a longish fling with David Essex during the run of this show, and then went back to Cowell) played Maimiti. Directed by Michael Bogdanov, and choreographed by Christopher Bruce, this should have been a stunner of a show, but the critics panned it and I can’t remember much about it. This was the last show I was to see on my own for 16 years!

Well this show had a fairly mighty pedigree, so long as you like David Essex – he wrote the music and starred as Fletcher Christian. I do like David Essex – on records – but not on stage, where I feel he is wooden and expressionless, sadly. But there was more to this show than Mr Essex. Frank Finlay was Captain Bligh, whilst Sinitta Renet (yes, the Sinitta of So Macho fame, who had been going out with Simon Cowell, had a longish fling with David Essex during the run of this show, and then went back to Cowell) played Maimiti. Directed by Michael Bogdanov, and choreographed by Christopher Bruce, this should have been a stunner of a show, but the critics panned it and I can’t remember much about it. This was the last show I was to see on my own for 16 years!

With Miss D back in the UK, and us “going out” full time, our next show together was the new play by David Mamet, whose work I had admired for many years. Glengarry Glen Ross has come back recently, and felt like a much better play than our memory of this production, which is a difficult play to stage because of its uneven structure. Nevertheless I enjoyed it, whilst Miss D hated it. A strong cast included Derek Newark, Karl Johnson, James Grant, Kevin McNally and Tony Haygarth.

With Miss D back in the UK, and us “going out” full time, our next show together was the new play by David Mamet, whose work I had admired for many years. Glengarry Glen Ross has come back recently, and felt like a much better play than our memory of this production, which is a difficult play to stage because of its uneven structure. Nevertheless I enjoyed it, whilst Miss D hated it. A strong cast included Derek Newark, Karl Johnson, James Grant, Kevin McNally and Tony Haygarth.

1986 turned out to be a year of big shows with big reputations, and first of the big-hitters that year was undoubtedly this landmark play and production, which, fortuitously, had a change of cast just before we saw it, so that the lead role of Arnold Beckoff was played by the writer and All Round Significant Person, Harvey Fierstein himself. It will come as no surprise that he was sensational – the perfect combination of funny and sad with huge dollops of emotion throughout. Rupert Frazer, Belinda Sinclair and Rupert Graves all gave brilliant supporting performances, and the memorable role of Arnold’s mum was played to perfection by Miriam Karlin.

1986 turned out to be a year of big shows with big reputations, and first of the big-hitters that year was undoubtedly this landmark play and production, which, fortuitously, had a change of cast just before we saw it, so that the lead role of Arnold Beckoff was played by the writer and All Round Significant Person, Harvey Fierstein himself. It will come as no surprise that he was sensational – the perfect combination of funny and sad with huge dollops of emotion throughout. Rupert Frazer, Belinda Sinclair and Rupert Graves all gave brilliant supporting performances, and the memorable role of Arnold’s mum was played to perfection by Miriam Karlin.

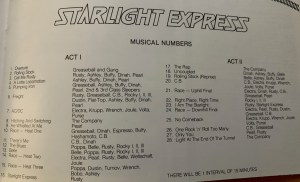

Starlight Express, answer me yes, are you real, yes or no? Definitely real to me, I absolutely loved this vast but intimate, brash but emotional show about little Rusty, the little steam engine who dreams big, and attempts to win the race to be fastest, so that he can steal the heart of Pearl, the first-class carriage. But Electra and Greaseball aren’t going to take that lying down. All on roller skates, of course, with aprons jutting out into the auditorium to bring the action even closer. A lovely score, with a few real highlights – Starlight Express, Light at the End of the Tunnel, and my favourite, He Whistled at Me. Yes, I know it’s for kids really, but you’d have to be really hard-hearted not to love it. The show had already been running for a couple of years, and our cast featured Kofi Missah as Rusty, Maria Hyde as Pearl, Lon Satton as Poppa, Drue Williams as Greaseball, and Maynard Williams as Electra. Only 11 days before we saw the show Maynard Williams (son of Bill Maynard) had appeared as the UK’s representative in the Eurovision Song Contest as lead singer of Ryder, with the song Runner in the Night. You won’t remember it.

Starlight Express, answer me yes, are you real, yes or no? Definitely real to me, I absolutely loved this vast but intimate, brash but emotional show about little Rusty, the little steam engine who dreams big, and attempts to win the race to be fastest, so that he can steal the heart of Pearl, the first-class carriage. But Electra and Greaseball aren’t going to take that lying down. All on roller skates, of course, with aprons jutting out into the auditorium to bring the action even closer. A lovely score, with a few real highlights – Starlight Express, Light at the End of the Tunnel, and my favourite, He Whistled at Me. Yes, I know it’s for kids really, but you’d have to be really hard-hearted not to love it. The show had already been running for a couple of years, and our cast featured Kofi Missah as Rusty, Maria Hyde as Pearl, Lon Satton as Poppa, Drue Williams as Greaseball, and Maynard Williams as Electra. Only 11 days before we saw the show Maynard Williams (son of Bill Maynard) had appeared as the UK’s representative in the Eurovision Song Contest as lead singer of Ryder, with the song Runner in the Night. You won’t remember it.

Shakespeare’s knockabout comedy was given a 1950s treatment in a brilliant production by Bill Alexander, and with stunning set design by William Dudley. My main memory of it is watching Mistress Page and Mistress Ford getting their hair done under one of those big old 50s/60s hairdo machines. With a cast that included Nicky Henson, Lindsay Duncan, Ian Talbot, Peter Jeffrey (as Falstaff) and Sheila Steafel as Mistress Quickly, you can guess that laughter was the top priority. A relatively big group of us went to see this – not only Miss D, but also my friends Mike and Lin and her mum Barbara. A good night enjoyed by everyone!

Shakespeare’s knockabout comedy was given a 1950s treatment in a brilliant production by Bill Alexander, and with stunning set design by William Dudley. My main memory of it is watching Mistress Page and Mistress Ford getting their hair done under one of those big old 50s/60s hairdo machines. With a cast that included Nicky Henson, Lindsay Duncan, Ian Talbot, Peter Jeffrey (as Falstaff) and Sheila Steafel as Mistress Quickly, you can guess that laughter was the top priority. A relatively big group of us went to see this – not only Miss D, but also my friends Mike and Lin and her mum Barbara. A good night enjoyed by everyone!

J B Priestley’s vintage comedy was brought to life in an effervescent production by Ronald Eyre for the Theatre of Comedy Company, with this immense cast: Bill Fraser, James Grout, Patricia Hayes, Brian Murphy, Patricia Routledge, Patsy Rowlands, Elizabeth Spriggs, and the real life couple of Prunella Scales and Timothy West. Fascinatingly, Patricia Hayes had appeared in the original 1938 production – although in a much more minor role. Three couples discover that they are not legally married and endure Victorian levels of embarrassment as a result. Dated but still fun.

J B Priestley’s vintage comedy was brought to life in an effervescent production by Ronald Eyre for the Theatre of Comedy Company, with this immense cast: Bill Fraser, James Grout, Patricia Hayes, Brian Murphy, Patricia Routledge, Patsy Rowlands, Elizabeth Spriggs, and the real life couple of Prunella Scales and Timothy West. Fascinatingly, Patricia Hayes had appeared in the original 1938 production – although in a much more minor role. Three couples discover that they are not legally married and endure Victorian levels of embarrassment as a result. Dated but still fun.

Never one to miss an opportunity to go to the London Palladium, this was the original London production of Jerry Herman and Harvey Fierstein’s enduring musical, adapted from the old French comedy film of the same name. George Hearn and Denis Quilley took the lead roles, but it was Brian Glover’s fantastic comic performance as the dreadful M. Dindon that stole the show. I know everyone loves the song I Am what I Am, and it is indeed a great number, but it’s not a patch on the wonderful The Best of Times which always gives me goosebumps. Totally and officially fabulous in every respect.

Never one to miss an opportunity to go to the London Palladium, this was the original London production of Jerry Herman and Harvey Fierstein’s enduring musical, adapted from the old French comedy film of the same name. George Hearn and Denis Quilley took the lead roles, but it was Brian Glover’s fantastic comic performance as the dreadful M. Dindon that stole the show. I know everyone loves the song I Am what I Am, and it is indeed a great number, but it’s not a patch on the wonderful The Best of Times which always gives me goosebumps. Totally and officially fabulous in every respect. Rambert had a two week season at Sadler’s Wells, with four programmes on offer in all, and over the course of two Saturdays we caught Programmes 1 and 3. Programme 1 featured Dipping Wings (Continual Departing) by Mary Evelyn, Soirée Musicale by Antony Tudor, Mercure by Ian Spink and Zansa by Richard Alston. Programme 3 was Glen Tetley’s Pierrot Lunaire, Christopher Bruce’s Ceremonies and Richard Alston’s Java, danced to the music of the Ink Spots. Hard to remember, but I think Programme 3 was the more entertaining. Rambert at the time had such brilliant dancers as Mark Baldwin, Lucy Bethune, Christopher Carney, Catherine Becque, Christopher Powney, and Frances Carty. Fantastic performances, and we continued to wear our Ballet Rambert t-shirts that we bought at the theatre for many years!

Rambert had a two week season at Sadler’s Wells, with four programmes on offer in all, and over the course of two Saturdays we caught Programmes 1 and 3. Programme 1 featured Dipping Wings (Continual Departing) by Mary Evelyn, Soirée Musicale by Antony Tudor, Mercure by Ian Spink and Zansa by Richard Alston. Programme 3 was Glen Tetley’s Pierrot Lunaire, Christopher Bruce’s Ceremonies and Richard Alston’s Java, danced to the music of the Ink Spots. Hard to remember, but I think Programme 3 was the more entertaining. Rambert at the time had such brilliant dancers as Mark Baldwin, Lucy Bethune, Christopher Carney, Catherine Becque, Christopher Powney, and Frances Carty. Fantastic performances, and we continued to wear our Ballet Rambert t-shirts that we bought at the theatre for many years!